Written by Angus Gibbs, Engineering Lead @ HubSpot.

The Workflows engine at HubSpot has to handle traffic from millions of workflows every day. Huge traffic spikes and slow response times from our dependencies are a fact of life. In this post, we’ll take a look at how we use Kafka swimlanes to keep Workflows fast and reliable.

_________________

Background

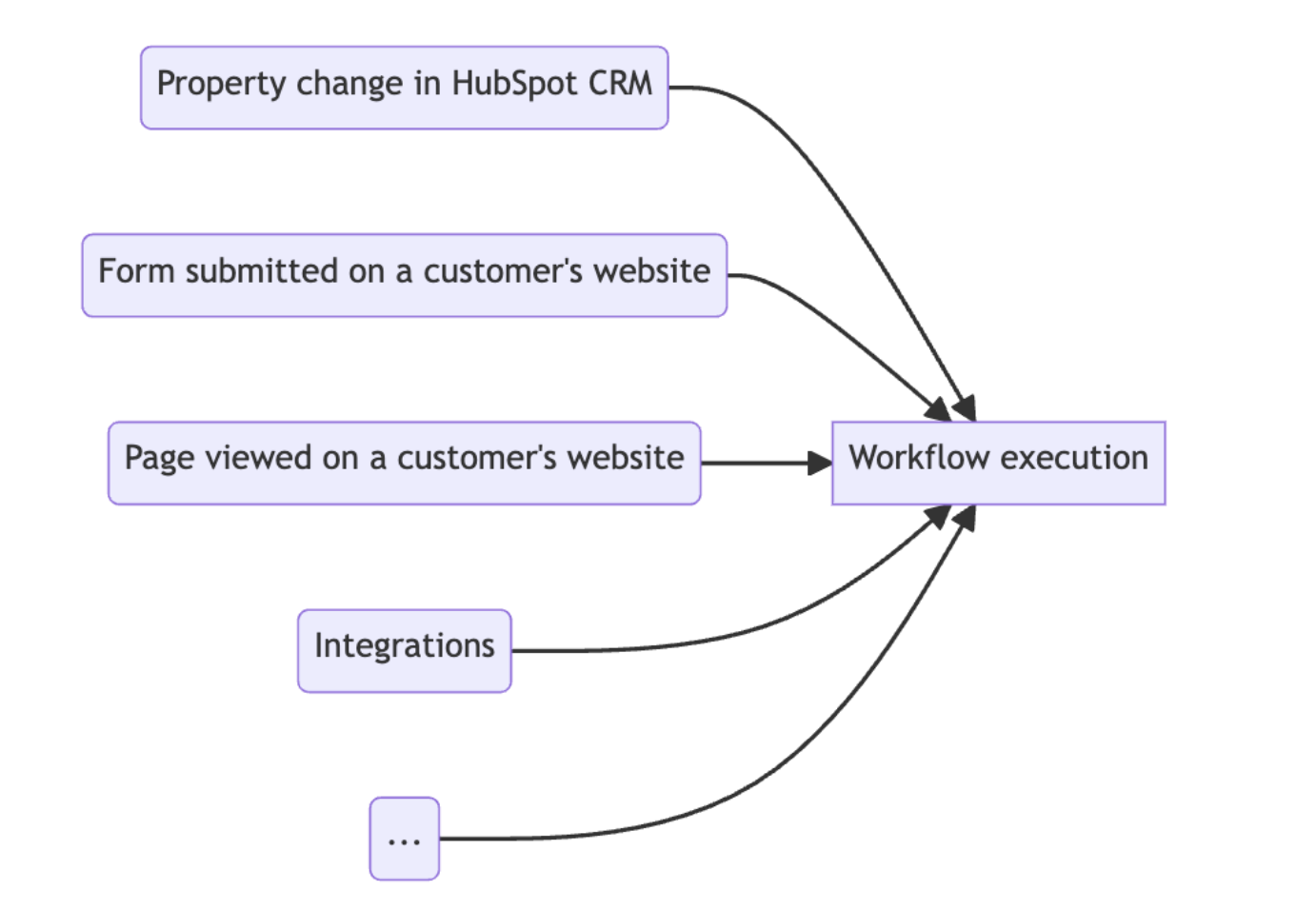

HubSpot’s customers use workflows to automate their business processes. Workflows are made of triggers, which tell the workflow when to “enroll” records to be processed, and a collection of actions, which tell the workflow what to do with those enrolled records. There are millions of active workflows, which collectively execute hundreds of millions of actions every day, and tens of thousands of actions per second.

Workflows engine overview

Once the workflow gets triggered, an enrollment is created and the workflows engine begins to execute the actions in the workflow. In theory, this could happen synchronously in the same process that received the trigger. However, at the scale that HubSpot operates, that approach would quickly break down: we don’t have control over when workflows are triggered, so if the triggers came in too quickly, we’d overflow our thread pools and start dropping enrollments. Not good!

Kafka to the rescue

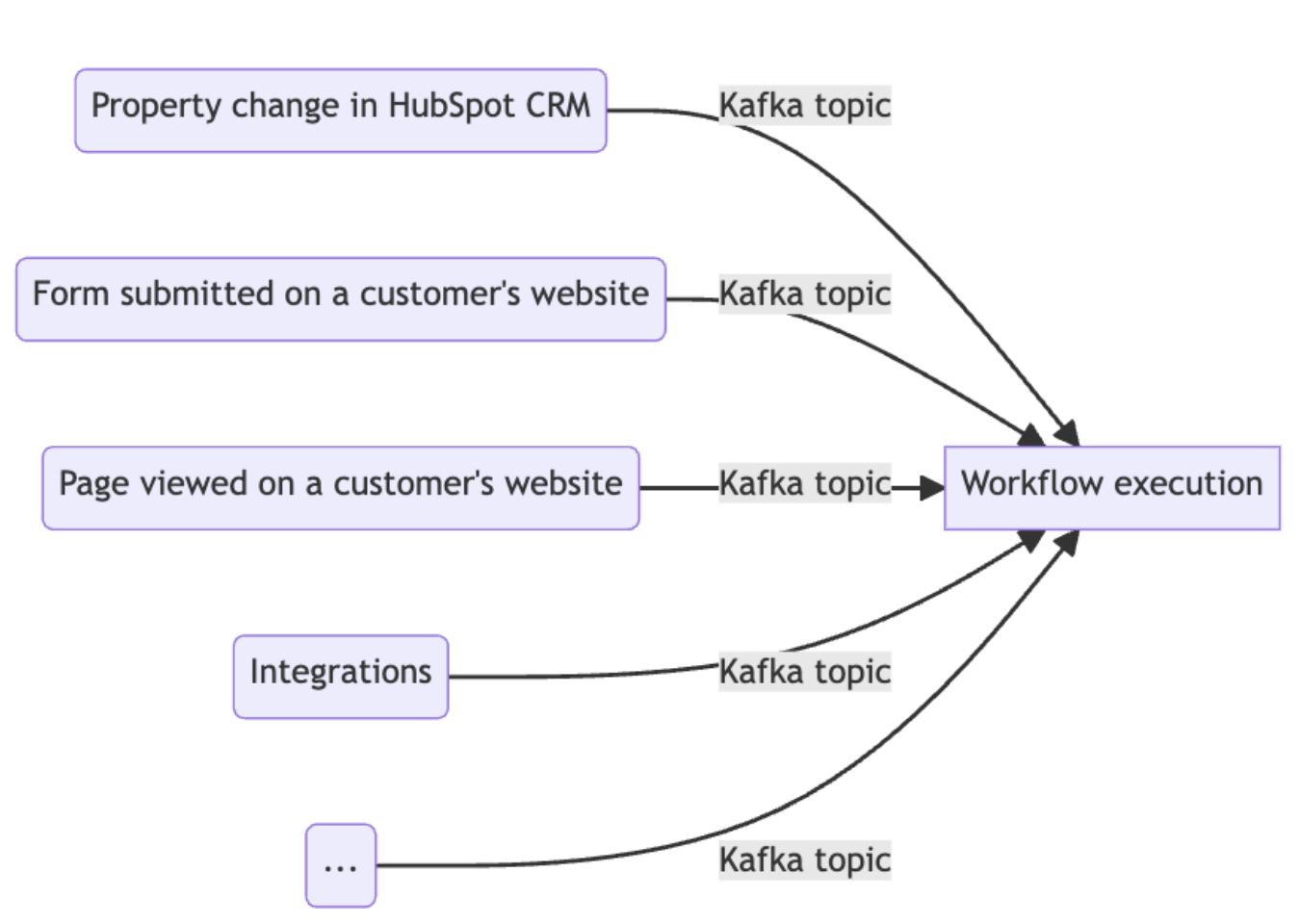

Instead, the enrollment and execution systems communicate using Apache Kafka, a queueing system that’s used heavily at HubSpot. Kafka allows us to decouple when a task is originally requested from when it’s actually processed; messages are produced onto a topic by a producer, and then consumed by one or more consumers. The producer and the consumer are independent of each other: the producer doesn’t know when the consumer will actually process the message, just that the consumer is guaranteed to receive the message.

Looking at our earlier diagram, we can see that each of those arrows are actually a Kafka topic:

Workflows engine with Kafka topics labeled

Now, we’ve solved the problem of trying to process every trigger synchronously: we can accept triggers as fast as they occur, and we’ll process them as fast as we can in our Kafka consumer. But we’ve opened ourselves up to a new problem: if we don’t process messages fast enough, our Kafka consumer will build up lag, meaning that there’s a delay between when the actions are supposed to execute and when they actually execute.

If there’s a sudden burst of messages produced onto our topic, there will be a backlog of messages that we have to work through. We could scale our number of consumer instances up, but that would increase our infrastructure costs; we could add autoscale, but adding new instances takes time, and customers generally expect workflows to process enrollments in near real time. So what do we do?

Enter, swimlanes

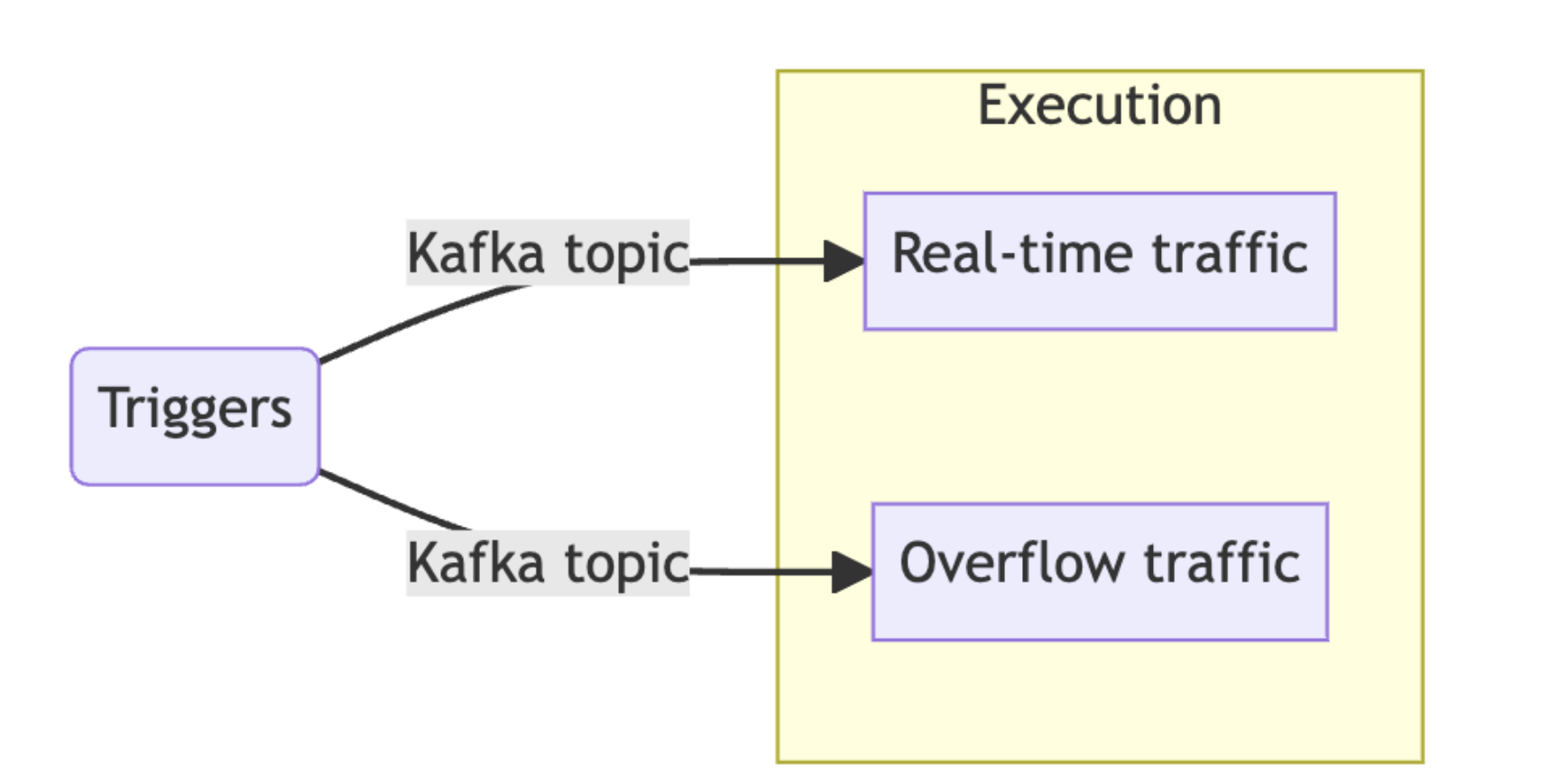

The fundamental problem here is that all of our traffic, for all of our customers, is being produced to the same queue. If the consumer of that queue experiences delays, then all of our traffic is delayed. Introducing a swimlane allows us to isolate slices of that traffic:

Swimlanes for the workflow execution system

Instead of sending all traffic to our “real time” traffic swimlane—where we want to minimize delays as much as possible—we can send some of our traffic to an “overflow” swimlane. The two swimlanes process messages in exactly the same way, but can build up delays independently. If we get a sudden burst of traffic that’s coming in faster than the real time swimlane can accommodate, we’ll protect the real time swimlane by sending excess traffic to the overflow swimlane.

At face value this might seem like we’re just moving the problem somewhere else—and in some ways we are—but this strategy has been widely deployed at HubSpot with lots of success. Usually only a small handful of customers are generating a burst of traffic at any point in time. By moving the traffic elsewhere we’re isolating those customers from the thousands of other customers with more stable traffic levels, providing a much faster experience for the majority of our customers.

There are many strategies that can be used to determine which swimlane to route a message to. In general, these can be classified into “manual” (reactive) and “automatic” (proactive) strategies. Automatic strategies reduce operational burden, since they don’t require any intervention from an engineer, but manual strategies are helpful too, since they give us an “escape hatch” if we ever need to reroute a subset of our traffic.

Automatically handling bursts

We know that we want to route bursts of traffic to the overflow swimlane, but how do we actually detect the bursts? It’s not always possible, but sometimes we can tell just by looking at the fields on the Kafka messages. For example, workflows has a feature called “bulk enrollment” that allows customers to quickly enroll millions of records into a workflow. We can look at the original enrollment source on the Kafka message, and if it’s a bulk enrollment, automatically route to the overflow swimlane. Another common pattern at HubSpot is to have a “backfill” flag on the Kafka message, to indicate that a message is being produced as a result of a one-off job that doesn’t need to be processed right away; this can also be used for swimlane routing.

Sometimes, though, we can’t tell just by looking at the message. In those cases, a rate limiter can be used. Rate limiters, such as a Guava RateLimiter, enforce a maximum rate at which some processing can happen. When we’re deciding which swimlane to route traffic to, we’ll check each message against a per-customer rate limit, and route traffic to the overflow swimlane once the rate limiter starts rejecting traffic.

Rate limits are made up of a threshold value (e.g. 250 requests) and bucket size (e.g. per second or per minute). Smaller bucket sizes respond more quickly to bursts of traffic, but can over-penalize small bursts. For example, if we have a rate limit of 250 requests/sec, and we receive 300 requests in one second and then no further requests, we’ll rate limit 50 requests even though the total amount of requests is pretty reasonable. To get around this, we can enforce multiple rate limits, with different thresholds and bucket sizes (e.g. one rate limit of 500 requests/sec and another of 1000 requests/min).

Setting the rate limit thresholds requires some domain knowledge. Generally we’ll look at our workers’ metrics when they’re under load, to get an estimate of their maximum throughput. Then, we’ll set per-customer rate limits below that threshold, to protect against individual customers dominating the overall capacity. It’s a good idea to make the limits configurable, so that they can be changed over time based on observed throughput and lag.

Other ways to automatically route traffic

So far we’ve only talked about swimlanes as a way to offload bursts of traffic, but they’re actually much more versatile than that. Since workflow execution traffic is very heterogeneous, we also leverage swimlanes to isolate “fast” traffic from “slow” traffic. Similar to how we look at the original enrollment source to decide which swimlane to route to, we’ll also look at what type of action we’re executing, and we’ll execute action types that generally take longer (e.g. custom code actions, which allow customers to write arbitrary Node or Python scripts) in dedicated swimlanes. We even have a system that can predict whether an action will be slow based on its historical latency, which might get its own blog post one day 😉.

Manual traffic routing

All of the automatic routing means that most of the time, the workflows engine runs on autopilot. But every now and then an issue comes up that requires some manual intervention, and when that happens, we’re happy to have manual routing options. One manual strategy that we make use of frequently is a configurable list of customers to forcibly re-route. If something goes wrong for a specific customer—for example, actions executing particularly slowly—we can isolate that customer into its own swimlane, to reduce the impact of the issue while we investigate and resolve the problem.

In order for manual routing to be effective, it’s important to have good visibility into our systems—that way we know what subset of traffic needs to get rerouted. Luckily for us, HubSpot has world class internal developer tooling, which makes it easy to uncover problems by searching our logs or looking at our metrics. We record custom metrics that give us execution latency across many dimensions (e.g. action type), and we have logging that tells us what’s happening for every action.

Conclusion

Kafka is a powerful tool for asynchronous task processing, but because queues are shared infrastructure, there’s no isolation between messages that are produced to the queue. Swimlanes give us a way to isolate traffic. We’ve laid out the basic principles behind our swimlanes, but these patterns can be applied in many different ways. Altogether we have about a dozen different swimlanes powering our execution engine, helping to keep workflows fast and reliable.

Are you an engineer who's interested in solving hard problems like these? Check out our careers page for your next opportunity! And to learn more about our culture, follow us on Instagram @HubSpotLife.