It’s a good time to be a SaaS company. We have tons of information at our fingertips on the metrics software-as-a-service companies should be tracking, including benchmarks for those metrics. But this wasn’t always the case; I remember when "Customer Acquisition Cost" and "Lifetime Value of a Customer" were buzzwords. Now, we have more acronyms than we know what to do with and those two only scratch the surface on how your biz is doing. No offense, CAC and LTV, but we need to dig a little deeper.

It’s a good time to be a SaaS company. We have tons of information at our fingertips on the metrics software-as-a-service companies should be tracking, including benchmarks for those metrics. But this wasn’t always the case; I remember when "Customer Acquisition Cost" and "Lifetime Value of a Customer" were buzzwords. Now, we have more acronyms than we know what to do with and those two only scratch the surface on how your biz is doing. No offense, CAC and LTV, but we need to dig a little deeper.

There’s one piece of the SaaS metrics puzzle we, HubSpot’s Sidekick team, rely on heavily and that’s gross margin-adjusted payback period. It might sound like total Greek at first, but payback period is a simple metric (it is, I promise) that helps businesses keep acquisition, retention, and conversion costs in check. When you spend money to acquire customers, you expect to make that money back ... one day. Payback period tells you how long it’ll take for that to happen and the "gross margin-adjusted" piece is a valuable filter for freemium products like Sidekick.

(Payback) Time is Money

Imagine you just bought a house and plan to rent it out. You paid a certain amount up front to purchase the property (let's assume you’re not taking out a mortgage) and will collect rent from your tenant every month. If it takes 100 years for you to break even, the property probably wasn’t a great investment. But, if it only takes two months, you'd be crazy not to make more of those investments, right?

For SaaS companies, it's the same situation: we pay up front to acquire a user and if that user ends up becoming a paying customer, they’ll generate value back to the business over time. Knowing whether that’ll take 100 years or two months is crucial because subscription-based business is risky. You’re investing money that you might never see again; customers could churn before you break even and a good chunk of your users will never become paying customers. That’s why SaaS companies aim to get their money back quickly; a payback period of about 12 months is a good goal. That way, customers are paying for themselves and becoming profitable within a year.

So, how do you figure out what your payback period is? Easy peasy. Divide CAC by your Monthly Recurring Revenue (MRR) per customer, (the amount customers pay for your product or service, like “rent” for a property owner.) If you don’t know what your CAC is, shame on you. There’s a good primer here for calculating it, but basically it’s just the sum of what you spend on sales and marketing in a given time period (e.g. advertising, commissions, salaries, overhead) divided by the number of customers you acquired in that same time frame. After that quick math, you’re left with the number of months it’ll take you to break even ... sort of. This is where payback period gets interesting.

Money Costs Money

Say you have to pay the electric bill out-of-pocket on the house you bought. Or, maybe you have to spend your own time maintaining the yard or dealing with the tenants. These are real costs that we call costs of goods sold (COGS) and they affect the margin of your property. Though you collect $Y/month on the property, you spend $Z of that to keep things running; you have to factor that into your equation for your payback period to be truly reflective of what your output is. This is where “gross margin-adjusted” comes in.

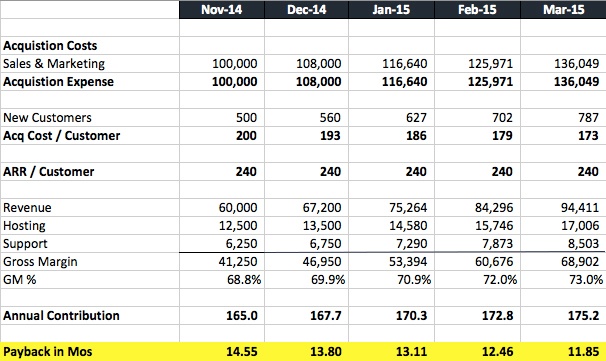

Keeping a product up-and-running and on the cutting edge, especially as your customer base grows, is a big investment. In the SaaS world, our COGS aren’t electric bills or landlord to-dos, but hosting and customer support. So, while gross margin-adjusted payback period sounds scary, it’s really just how long it takes to break even given all the costs that go into acquiring customers (not just marketing and sales). Here's what it looks like in a spreadsheet:

(fake data)

You can see here that the gross margin is 68.8%, so to calculate our gross margin-adjusted payback period, we do the same equation as above only the MRR value should be multiplied by that percentage:

200/((240/12)*0.688) = 14.55

Not So Fast, Freemium

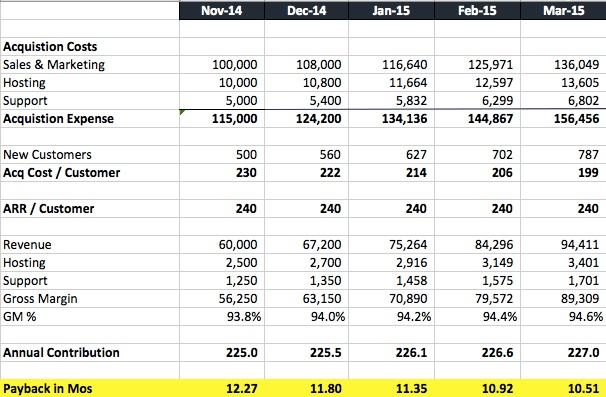

For freemium businesses like Sidekick, factoring in gross margin is crucial for two reasons: we spend way less on "traditional" acquisition costs like sales and marketing, and most of users aren't generating any revenue. Naturally, those conditions are going to cause a kink in the payback period plan if we're only looking at CAC and MRR/customer. One approach we like for this scenario is to determine what the usage breakdown between free and paid users is and to split hosting, and any other COGS, between acquisition and expense.

(fake data)

In this table, you can see there are line items for hosting and support in two places: under Acquisition Costs and Acquisition Expense. The total cost of hosting, capital expenditure, and support are broken across the two categories according to the ratio of active usage in each of the "Free" (acquisition) and "Paid" buckets.

In short, you get a nice adjustment to your numbers by accounting this way, but it’s really only fair if you’re truly running a freemium model where your user base isn’t valuable until you invest time and resources into getting them heavily engaged with your product. In an inside or field sales model the analog would be investing in marketing campaigns and sales touches - in freemium, on the other hand, those costs are replaced and your payback performance should take that into account.

Putting Payback to Work

Now that you’ve got your fancy new gross margin-adjusted payback period, how should you use it to drive your business and product strategy? The truthful answer is, well, it depends. Every company is different and will have their own approach to defining and using metrics like this. But, there is a simple takeaway here that can help align your sales, marketing, and engineering efforts: Use your payback time as a thermometer for your business to diagnose what’s working and what’s not.

If your payback period is under 12 months, consider investing in and experimenting with new and/or increasingly aggressive acquisition approaches. On the other hand, if payback is getting away from you (18 months or more) you should consider choosing an internal metric that could be weighing you down and optimizing it aggressively. The candidates to hammer on here include: churn rate, acquisition costs, user or lead conversion rate, and your average sale price (ASP). When all the moving pieces are aligned and working, you’ll find your sweet spot.

At the end of the day, you can become a landlord or an entrepreneur overnight but you won’t be very good at either unless you know your numbers. Hopefully, this was a helpful look at calculating payback period and why it’s so important for SaaS companies specifically. For more guidance on tracking SaaS metrics, check out this blog from David Skok and let me know in the comments what would be a helpful post to write next on this topic. Happy to do it (with the help of HubSpot’s finest, of course).

How do you and your team determine whether your product and sales efforts are cohesively successful?